Luther’s Life and Leadership

This essay was first delivered as a talk to a group of Classical School Administrators at an Association of Classical Christian Schools Regional at Arma Dei Academy in Highlands Ranch, Colorado.

Did you know that MLK Jr was named after Martin Luther? Although the American civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. (1929-1968) never cited the German theologian Martin Luther (1483-1546), the 16th century German’s courage inspired King’s father in the 20th century civil rights cause in Atlanta, Georgia. In fact, Martin Luther King Jr. was originally named Michael until he was 5 years old, but his father changed his own name and his son’s after visiting Berlin, Germany in 1934 for a Baptist preachers’ conference. King Sr. had been alarmed by seeing Hitler’s racially-motivated rise to power occurring in the very same land where Luther nailed the 95 Theses in 1517 and gave his “Here I stand” speech at the Diet of Worms in 1521 [1]. Luther’s story gave King Sr. eyes to see his own situation in racially divided Atlanta with greater clarity and courage. King Sr. was compelled to challenge authority and the status quo after hearing of Luther being excommunicated by the Pope yet being loved by the people. Christian school administrators, like King’s father at a Christian conference almost a century ago, could experience a similar awakening to face the problems waiting for you when you return to your desk.

Luther’s story is especially helpful for educators. Luther had a dramatic impact on the education of his day by translating the Bible into German, promoting literacy via printing books and catechisms, and starting schools for German children. Luther used his influence to promote a biblical worldview in education. He wrote, “A city’s best and greatest welfare, safety, and strength consist in having many able, learned, wise, and honorable and well-educated citizens” [2]. Luther argued that if Germany were to prosper, the educational standards must be raised in order to carry forward the ideals of the Reformation. He pointed out that Rome prospered for a time, because they had capable men for every position. 500 years later, Luther’s voice still invigorates.

Prefaratory Remarks

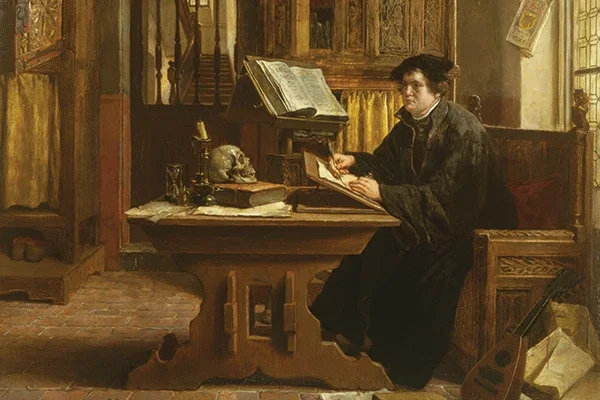

While Luther was far from perfect, he is a hero worthy of imitation for Christian leaders. Three milestones in Luther’s life deserve consideration: his Tower Experience in 1515, the 95 Thesis in 1517, and the Diet of Worms in 1521. Luther is a hero worthy of imitation for His undivided loyalty to Christ and the Scriptures. Not all share this view obviously. Erasmus viewed him as zealous but misguided. Erasmus wrote in 1524, “Luther has a fiery and impetuous temperament. In everything he does, you can recognize the ‘anger of Peleus’ son [i.e., Achilles] who knows not how to yield” [3]. Erasmus viewed Luther as a troubler of the church who was doing more harm than healing via the extreme views in his writing and his rhetoric. Luther’s moment in history became marked by the extremes, and it can serve as great training to exegete his reactions to his trials. Luther was not looking for a fight but was dragged into one, and he stood his ground. Most teachers and administrators were not really looking for classical but got dragged into it. Classical education is a form of learning that focuses on exposing children to the best that’s been said,thought, and done in literature, history, art, music, math, science and languages. Proverbs 13:20 describes our method with students, “Those who walk with the wise become wise but a companion of fools will suffer harm.”

Reformation historians are divided on what to make of Luther’s leadership. Ronald Bainton labels him a reluctant rebel when he says, “Luther had not intended to break the Church, but his insistence on the Gospel inevitably led to division” [4]. Heiko Oberman makes Luther’s life an issue of conscience and calling and writes, “There is no clear dividing line between the two churches in Luther’s thought; the Church is one, but its unity is not identical with the unity of the institution” [5]. In other words, Luther’s undivided loyalty to Christ and the Scriptures brought the division to a church with hidden fractures. On the other hand, Alister McGrath in Christianity’s Dangerous Idea: The Protestant Revolution argues, “In the end, not even the personal authority of Luther could redirect this religious revolution, which anxious governments sought to tame and domesticate” [6]. Whether one views him as a saint or schismatic, he is part of the Great Conversation and merits the attention of today’s school leaders. We, too— if we truly lead— will generate diverse responses. This is the nature of doing Gospel ministry; which is what you’re doing as a Christian school adminstrator. I am not sure if there’s one key to success, but there’s one key to failure— try to please everybody all of the time.

The Tower Experience 1515

Dr. Albert Mohler once said in a lecture on leadership that, if he could go back to the Reformation, he would study with the always-serious John Calvin while living with the always-animated Martin Luther. Luther publicly shared a series of ‘inner upheavals in his quest for God’ that make him personally relatable for many who have had internal religious conflict– much different than Calvin who was hardly ever autobiographical [7].

Luther’s first acute religious crisis occurred at age 21 while he was at University in Erfurt when he was caught in a lightning storm that frightened him to his bones. He ducked under a tree, clutched onto a rock, and cried out Saint Anne to save him. For Luther, there was such a great distance between him and the bolt-throwing God of justice. He needed a mediator between himself and the Creator. He knew not of the graciousness of the God man Jesus Christ who is the one mediator between God and man. He prayed to Saint Anne, the patron saint of miners, for protection. He knew of Saint Anne through his devoted father, Hans, who owned a few foundries in the mines. In lieu of protection from Saint Anne, Luther vowed to enter the monastery. While most would abandon the vow after the storm cleared, Luther entered the most severe of the monasteries, the Augustinians, just two weeks later. He did not consult with his father or friends but followed his conscience, a theme that occurs throughout his life. Conscience and the Scriptures would come to hold a place of greater than papal authority for Luther. The lightning storm made God’s authority vividly real to him for a moment, and he could not shake the divine gnaw on his conscience. He had to try to find a way to close the gap between him and God. Becoming a lawyer could not scratch the itch for Luther any longer. An alarm bell was going off in his conscience that he could not continue to sleep through. Many of those in Classical Christian education also entered into their roles not because of convenience but calling.

This fearful insecurity he felt regarding the God who he dreaded motivated his devoted performance as a monk. Luther stated, “If ever a monk got to Heaven by monkery, it was I” [8]. As an Augustinian monk, Luther submitted himself to fasting, rough clothing, poverty, and night prayer vigils. Until his death at age 62, Luther suffered from various digestive issues which he attributed to his 5+ years of a rigorous fasting regimen.

Five years after entering the monastery, Luther was sent to Rome to fulfill his monastic duties where he became disillusioned with the corruption of the church. In Rome, he encountered a great variety of relics: pieces of Moses’ burning bush, the chains of St. Paul, thorns from Christ’s crown, and the bones of the apostles. Bainton comments on Luther’s trip to Rome that, “Disillusionments of various sorts set in at once” [9]. Luther observed flippant unbelief, levity and abysmal ignorance from among the Italian clergy. However, he was not ready to abandon his lifelong church based upon the occasional corruption from her priests. Before departing from Rome, Luther climbed each stair of the 28 steps of Pontius Pilate’s staircase saying an “Our Father” in hopes of releasing his Grandpa Hein from Purgatory. Luther was still in chains, not ready to bring reform. He viewed God as a distant authority that demanded more from Luther. This produced great anxiety and even despair and depression for Luther. Understanding Luther’s story helps against creeping legalism that could easily enter into a school culture.

The disillusionment and even despair started while Luther was in the monastery but was accelerated when Luther became a lecturer and then later a full professor of theology at the University of Wittenberg. As a professor, it was his practice to diligently study the Psalms, Hebrews, Romans, and other books of the Bible in their original languages and then make comments to his students. He used Erasmus’ NT Greek translation and deployed the tools of learning he had acquired in his humanist Liberal arts studies. Similar to Calvin and the other Reformers, Luther valued a return to the original sources (ad fontes) in their original languages of Hebrew, Greek, and Latin rather than a naive reliance upon established tradition. This phrase ad fontes is where Luther, Erasmus, and us today overlap. It matters which books rhe grammar kids read and someone should ensure they’re exposed to the best. Because of his classical education, Luther was equipped to think for himself and capable of meeting any intellectual challenge. Despite his intellectual abilities, Luther was terrorized by the righteousness of God and lived in constant dread of God’s justice.

Given his intellectual ability, Luther was sent from among the Augustinians to assume a lectureship, complete his Doctor of Theology, and then take a professorship at the new German university. Luther remained plagued by a view of Christ as a just avenger rather than a gracious redeemer despite his time in the Scriptures. Bainton writes that Luther “tried the way of good works and discovered that he could never do enough to save himself” [10]. He was never able to assuage ‘the anguish of a spirit alienated from God.’ Luther went to great lengths and even went to confession for as long as six hours on one occasion. Luther had reached a point of spiritual exhaustion after a decade of keeping his vow as both a monk and a theologian. Far be it from today’s classical Christian schools to assume that Luther’s early legalism could not occur in our students. Legalism is relying upon our own imperfect obedience rather than relying on Christ’s perfect obedience.

In 1515, Luther had an evangelical experience (commonly referred to as the Tower experience while studying Paul’s epistle to the Romans and considering the phrase, “the justice of God.” Luther writes, “My situation was that, although an impeccable monk, I stood before God as a sinner troubled in conscience, and I had no confidence that my merit would assuage him.” Luther could not find peace through his own efforts. Luther continues, “Night and day I pondered until I saw the connection between the justice of God and the statement “the just shall live by his faith.” Then I grasped that the justice of God is that righteousness by which through grace and sheer mercy God justified us through faith. Thereupon I felt myself to be reborn and to have gone through the open doors into paradise… this passage of Paul became unto me a gate to heaven” [11].

It took a lightning bolt and then 10 years of anguish to settle the score with God through the blood of Christ for Luther. This experience gave rise to the importance of the doctrine of justification by faith alone, not faith and works. Paul writes in Galatians 2:16, “yet we know that a person is not justified by works of the law but through faith in Jesus Christ, so we also have believed in Christ Jesus, in order to be justified by faith in Christ and not by works of the law, because by works of the law no one will be justified.” For Luther, this is the doctrine on which the church collapses or falls, and the same is true for today’s biblically grounded classical academies.

This doctrine of Sola Fide became known as one of the five solas of the Reformation and taught that man is justified by faith alone, not by works of the law. This first event came to be his defining moment, and it was always his signature move to appeal to Christ, the Scriptures, and his conscience. Paul writes in Galatians 1:7 “not that there is another one, but there are some who trouble you and want to distort the gospel of Christ.” The troublers of the church were the ones in authority during Luther’s day. In the church in Galatia, some were teaching that one must become circumcised before they could be justified. Luther comments, “Mark here diligently, that every teacher of works, and of the righteousness of the law, is a troubler of the church , and of the consciences of men” [12]. God became most real to Luther not via a mystical lightning bolt experience or a divine encounter during a fast but via wrestling through the Scriptures and relying upon Christ. That’s where the gap closed between his head and heart. The same could be said of Spurgeon, of Augustine, and many other Christian heroes.

Classical Christian academies do not want their students to have the same experience as Luther where they spend their K-12 years viewing God purely as a distant and demanding authority but not a gracious and sympathizing redeemer. For Luther’s moment, Galatians and Romans were paradigmatic in explaining justification by faith. In these letters to specific congregations, the needed correction was against legalism. What about your school culture? Is it harsh and legalistic with knuckles wrapped for missed Latin declensions. Some school cultures will need to draw from Corinthian letters to find correction against lawlessness instead of legalism. Some Christian kids grow up and think that God is an authority that wants to destroy any attempt at fun. Luther drank beer, left the monastery, got married, and had six kids (one died in infancy and another at 13). He enjoyed life yet he also fought against authorities troubling the consciences of others. He was adamant that ordinary Germans could see the freedom that was available to them through faith, rather than works-based righteousness. So maybe having dances at your school, enjoying some athletic competition, and going on an 8th grade retreat are part of our mission to create Christian freedom and joy. Creation is meant to be enjoyed as good.

With regard to Sola Fide, one more historical lesson merits consideration. Within a classical Christian school are various stripes of Evangelical families, and the main reason that they choose the academy is for its Christian philosophy, for the alignment with the family’s faith and virtues. To prevent unnecessary conflict, it is helpful to know that some Christians emphasize the head, others the heart, others the hands, yet all matter and nobody is perfectly balanced. Although Luther started with a focus on spiritual duty as a monk (spiritualist), he became a diligent student of the Scriptures as a professor (scholastic), and was pulled into becoming a social reformer (activist). Nowadays, the mystically-minded and the theologically minded overlap very little on Sunday, but their kids go to the same school Monday through Friday. It is interesting to note that the Reformation grew out of the spiritual and mystical ethos of monasticism but then he entered into theology which is driven by logic and philosophy and debate. There is no need to place a strong dichotomy between scholasticism’s logical emphasis on disputation and mysticism’s focus on experiencing the love of God. In the Middle Ages, it was difficult to determine whether someone had an intellectualist approach to Christianity or a more mystical one, because both were held together. Similar to Jonathan Edwards, Luther’s followers tended to fragment into groups after his death, because subsequent leaders were not able to hold these respective emphases together. While one of the unintended consequences of the Reformation over the past 500 years has been splintering into respective churches, the Academy can be a place where spiritualist mystics, intellectual scholastics, and culture warriors can happily coexist with a Sola Fide center. I also think our Grammar teachers and Rhetoric teachers, who differ in emphasis due to their respective duties, can learn from one another because of their shared creed. Sola Fide evangelicals who practice Sunday differently can unify Monday through Friday.

The 95 Thesis 1517

Now that Luther had grown comfortable under the authority of God through faith in Christ, he had a mission to challenge the abuses of the spiritual authorities around him. He really was in a pickle, because he was fully convinced that the church was in error. The circumstances leading up to the 95 Theses event was the swarm of troubled masses purchasing indulgences in response to Yohan Tezel declaring, "Every time a coin in the coffee rings a soul from purgatory springs.” For Luther, Tezel posed a threat to the Gospel that brought Luther peace. Luther had discovered that grace was a gift freely given by God, not a merit to be purchased by men. Luther wrote, “They preach only human doctrines who say that as soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs” and “Therefore, those preachers of indulgences are in error who say that by the pope’s indulgences a man is freed from every penalty, and saved” [13]. For the Church, they believed that they had authority to sell indulgences based upon papal precedent affirming indulgences in both 1476 and 1413. Every leader faces a Tezel at some point that is perceived as a threat to the preservation of the mission. These are the people that keep you up at night, and on occasion, they may be a real threat like Tezel was.

Tezel deployed the heights of his rhetoric to trouble the people of Wittenberg, “Have you considered that you are lashed in a furious tempest amid the temptations and dangers of the world, and you do not know whether you can reach the haven, not of your mortal body, but of your immortal soul? … Listen to the voices of your dear dead relatives and friends, beseeching you and saying pity us pity us we are in dire torment which you can redeem us for a pittance. Bainton writes that “so much money is going into the coffer of the vendor that new coins have to be minted on the spot” [14]. Given his newly forged view of God, this was inexcusable, so Luther placed 95 arguments against this practice (and other items) on the church door of Wittenberg. Luther had written in Latin so that a disputation could take place between him and the other professors at Wittenberg. However, a couple of students had the theses translated to German for distribution. Within a year, the theses had gone viral and Luther was the most famous man in Germany. In his theses, Luther had accused the church of blasphemy. Luther’s reaction was measured and studious and so should your responses be to problem people. Tezel was not just a pest to be tolerated but a heretic to be confronted, because he was attacking the gospel that brought freedom. In the theses, it is worth noting that Luther confronted the issue, not the individual.

Bainton calls Luther a reluctant rebel. Pelikan writes in Obedient Rebels that Luther’s protest was “not as a revolutionary, nor even as a protesting critic, but primarily as a member of the church, as one of its doctors and professors” [15]. He was a monk and a professor that was following the leading of the Scriptures and his conscience. Luther had written in Latin. Tezel had come to Luther’s neighborhood and was troubling the consciences of his flock. Luther was not a troll waiting for a fight with a critical spirit but was being a good shepherd. He had no choice but to respond. Luther writes, “If I profess with the loudest voice and clearest exposition every portion of the truth of God except precisely that little point which the world and the devil are at that moment attacking, I am not confessing Christ, however boldly I may be professing Him. Where the battle rages, there the loyalty of the soldier is proved; and to be steady on all the battle front besides is mere flight and disgrace if he flinches at that point” [16].

Luther used his authority as a professor to expose the heresy of hawking indulgences. Part of being in authority is directing the school community and protecting the school community. As a teacher, Luther had done his research to produce 95 points that expressed his disagreement. While we likely do not need to have 95 points, this is part of the job of a leader– to develop a perspective on a controversial issue that is impacting your students, teachers, and families. It may be an admissions policy or a cultural trend or a decision on school security. In an age that values keeping the peace at all costs, the 95 theses moment is a model for how to respond to someone sabotaging the work God has called you to do. Luther was placed in a situation where false teaching was rampant and innocent people were being taken advantage of to their peril. Sometimes, a dog needs to bark because his master is being attacked.

The Diet of Worms 1521

Within four years, Luther was despised by the papacy, adored by the common German, and considered polarizing by the Erasmians in the middle. Luther’s controversial status had reached the boiling point by 1521. He had defiantly debated various representatives of the Church, burned a papal bull in broad daylight, and reached the breaking point with Rome. None of us will face a dramatic situation quite the same as Luther, and we should not go looking for persecution or make people hate us of because of avoidable conflict. Choosing uniform colors or a mascot does not carry the same weight as the famous ‘here I stand’ moment Luther is about to face.

Despite the many opponents, Luther had gained the support of Frederick the Wise, the elector of Saxony who had offered him protection as he became increasingly polarizing. Similar to Joseph having Pharaoh’s support, Luther had a degree of protection against Rome. In Luther’s case, it was not his networking acumen or conference attendance that landed him Frederick’s protection. It was God’s providence that gained the backing. If you need help financially, or if you need certain legislation, trust the Lord. Sometimes you are Joseph with a supportive pharaoh and other times you are Moses and the new pharaoh does not care about Israel. You get what you get and you don’t throw a fit.

In 1521, he was set to face Emperor Charles V on his home turf of Worms, Germany for a diet (assembly) before those who had condemned him. This was not like the debates he had previously to express his views and demonstrate his biblical and theological mastery. This was to be a public hearing and it would be his last chance to make peace with the church that had reared him.

At the Diet, Luther was outnumbered with about 200 high ranking Roman clergy with a minority of Luther supporters gathered as well. Luther was ready for a debate like he had before but this was a trial. Luther’s books were heaped on a table, and he was asked to recant what he had written against the church. One thing you have to appreciate about Luther is how prolific of a scholar he was so early in life. From age 33 to 37, he wrote commentaries on Psalms and Romans and three books still read today: The Babylonian Captivity of the Church, To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation, and The Freedom of the Christian. In Babylonian Captivity, Luther wrote in 1520, “I say that neither Pope nor bishop nor any other man has the right to impose a single syllable of law upon a Christian man without his consent. For where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is liberty." For Luther, Christian authority should be used to create liberty, not captivity. He expands on this in The Freedom of the Christian when he wrote, “A Christian is a perfectly free lord of all, subject to none. A Christian is a perfectly dutiful servant of all, subject to all." The Christian is free from the tyranny of the law through faith yet also free to serve out of love for God and others. Luther was dismantling Roman hierarchy and emancipating the common man from the authority of the Roman Church. He had a great reverence for authority.

When asked if he would recant his works, Luther asked for a day to consider the question. He spent a day in fear and trembling praying utterly relying upon God to sustain him.

Upon returning, the frustrated Emperor Charles asked again, “Will you recant?” Luther responded, “Unless I am convinced by the testimony of Scripture or by clear reason (for I do not trust either in the pope or in councils alone, since it is well known that they have often erred and contradicted themselves), I am bound by the Scriptures I have quoted and my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and will not recant anything, since it is neither safe nor right to go against conscience. I cannot do otherwise. Here I stand. I can do no other. God help me. Amen.” Luther had grown up under the authority of the Church and now he was opposing the Church under the authority of Scripture. This stand gave rise to what’s known as the doctrine of Sola Scriptura: the Bible is the sole authority for Christian faith and practice. The Roman church had wrongly assigned infallible authority to papal authority and Church tradition. Luther empowered ordinary German believers to obey Scriptures and their conscience rather than Church tradition and papal authority. The way you prepare for the big moments is being consistent in the little moments.

For Classical Christian educators, this begs the question, “What do we do with the classics, tradition, and reason?” On the surface, it seems like Luther denied them. This tension is resolved by understanding that the phrase is Sola Scriptura, not Solo Scriptura. Luther emphasized Scripture alone as the final authority, but he was not saying Scripture only. Creeds, tradition, human reason, and human experience all must be tested by the Scriptures. The classics, tradition, and human reason still hold authority for the believer in Sola Scriptura, just not equal authority with the Bible in matters of Christian faith and practice. Given the classical Christian emphasis on truth, goodness, and beauty as well as the liberal arts tradition, we have to make a few important distinctions in order to lead faithfully within the sphere of the Academy. We rejoice in truths revealed in philosophy and the sciences as well as beauty in literature and fine art.

Luther wrote of Aristotle, “I should be glad to see Aristotle’s books on Logic, Rhetoric, and Poetics retained or used in an abridged form; as textbooks for the profitable training of young people in speaking and speaking and preaching. But the commentaries and notes should be abolished” [17]. Luther affirmed the value of Aristotle’s logic and rhetoric but denied his metaphysics on the ground that he was encroaching upon God’s authority to describe fundamental reality and existence. It was Luther’s view that much of Aristotelian philosophy encroached upon the jurisdiction of theology. The implication of this is especially important for Senior Thesis where students draw from the social sciences as well as philosophical sources within the Great Conversation. Students should be taught how to test these things against Scripture to find areas of continuity and discontinuity. As believers in Sola Scriptura, we need not restrict our insights to merely the book of Scripture but must also be open to the book of nature. The Scriptures do not impose on the book of nature but rather illuminate them much like light causes color to be more vivid.

With regard to tradition, we can warmly affirm the quote from Gustav Mahler, “Tradition is the preservation of the fire, not the worship of the ashes.” What Luther opposed was the Roman accretions that distorted the clarity of the Gospel. Luther’s appeal was a reformation, not a revolution because he appealed to antiquity. An appeal to the past is the right way to cause change for the future. In past generations, people shared a strong cultural assumption that older is better than newer. In our Academies, we are not antiquarian but place a value on things that are both old and valuable. Therefore, the liberal arts tradition is fair game. In fact, an awareness of what multiple generations have approved strengthens our reasons, expands our human experience, and enhances our appreciation of the Scriptures. Luther was neither an innovator nor a revolutionary.

Luther was no biblicist that was dismissive about the value of ancient languages and classical texts. Matthew Barrett writes in Reformation as Renewal, “Biblicism limits itself to those beliefs explicitly laid down in Scripture and fails to deduce doctrines from Scripture by good and necessary consequence.” Biblicism demonstrates a suspicion and dismissiveness to the book of creation; for our schools, we should fully embrace the fine arts, philosophy, mathematics, and all of the sciences as opportunities for wisdom, wonder, and worship. So read the book of virtues and tales about St George and the dragon. Take up The Chronicles of Narnia and enjoy the theology being smuggled in through story. Purchase a Bunsen burner, get a kiln— you are free to examine and enjoy the beauty God has set before us no matter where it’s found.

Conclusion

While justification by faith was the key doctrinal issue for Luther, a right view of authority was the institutional issue of the Reformation. If Luther was the first generation groundbreaking pioneer and polemicist, his successor Phillip Melanchthon was the second generation systematizer of Luther’s theology that would carry forth the reform. Luther’s pioneering leadership blazed a trail that second generation reformers like Melanchton, Calvin, Knox, and Zwingli would continue upon. For every school leader, their most important day within their academies is not the first but the last. Many leaders do not set up their successors for success, because they are not thinking about future generations. What you do today will echo on into the future of your school. Today, Luther’s German translation of the Bible is still in use, the denomination bearing his name is still in operation, and his catechisms are still regularly utilized around dinner tables. What legacy will you leave through your life and leadership?

Press on. Keep walking up hill despite the wind in your face. Even though your battle is different, you should labor diligently to get the right math curriculum in place. Take the time to make sure your board understands classical by reading good books together. Although you will probably not do polemics like Luther, your battles are not less important and there’s just as much at stake. Keep slugging. The Lord will reward you in due time.

Works Cited

King Institute. (n.d.). Introduction for Volume I: Called to Serve. The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute. Retrieved October 6, 2025, from https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/introduction-volume-i-called-serve?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Martin Luther, To the Councilmen of All Cities in Germany, That They Establish and Maintain Christian Schools (1524), in Luther’s Works, vol. 45, The Christian in Society II, ed. Walther I. Brandt (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1962), 347.

Desiderius Erasmus, Letter to Duke George of Saxony, 5 September 1524, in The Correspondence of Erasmus, vol. 10, 1524–1525, ed. and trans. R. A. B. Mynors and D. F. S. Thomson (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992), 27–28.

Roland H. Bainton, Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1950), 144.

Heiko A. Oberman, Luther: Man Between God and the Devil, trans. Eileen Walliser-Schwarzbart (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989), 250.

Alister E. McGrath, Christianity’s Dangerous Idea: The Protestant Revolution: A History from the Sixteenth Century to the Twenty-First (New York: HarperOne, 2007), 55.

Roland H. Bainton, Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1950), 6.

Martin Luther, quoted in Roland H. Bainton, Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1950), 34.

Martin Luther, quoted in Roland H. Bainton, Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1950), 35.

Martin Luther, quoted in Roland H. Bainton, Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1950), 36.

Martin Luther, Preface to the Complete Edition of Luther’s Latin Writings (1545), in Luther’s Works, vol. 34, Career of the Reformer IV, ed. Lewis W. Spitz (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1960), 336–337.

Martin Luther, Commentary on the Epistle to the Galatians (1535), in Luther’s Works, vol. 26, Lectures on Galatians, 1535, ed. Jaroslav Pelikan (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1963), 36.

Martin Luther, quoted in Roland H. Bainton, Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1950), 36.

Martin Luther, quoted in Roland H. Bainton, Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1950), 64.

Jaroslav Jan Pelikan, Obedient Rebels: Catholic Substance and Protestant Principle in Luther’s Reformation (New York: Harper & Row, 1964).

Martin Luther, Letter to the Elector of Saxony, 1521, in Luther’s Works, vol. 32, Career of the Reformer III, ed. Helmut T. Lehmann (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1967), 122.

Martin Luther, Table Talk (Tischreden), ed. Wilhelm Pauck, trans. Charles M. Jacobs (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1967).